Keith Haring at Tate Liverpool. Pop meets Politics.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Speed.

Not the drug; but the pace at which Keith Haring created his art. Incredible, fluid strokes applied at lightening speed to canvas, tarpaulin, brick, paper – you name it. Haring’s assured hand movements flitted across all these surfaces, creating a body of work that is instantly and globally recognised.

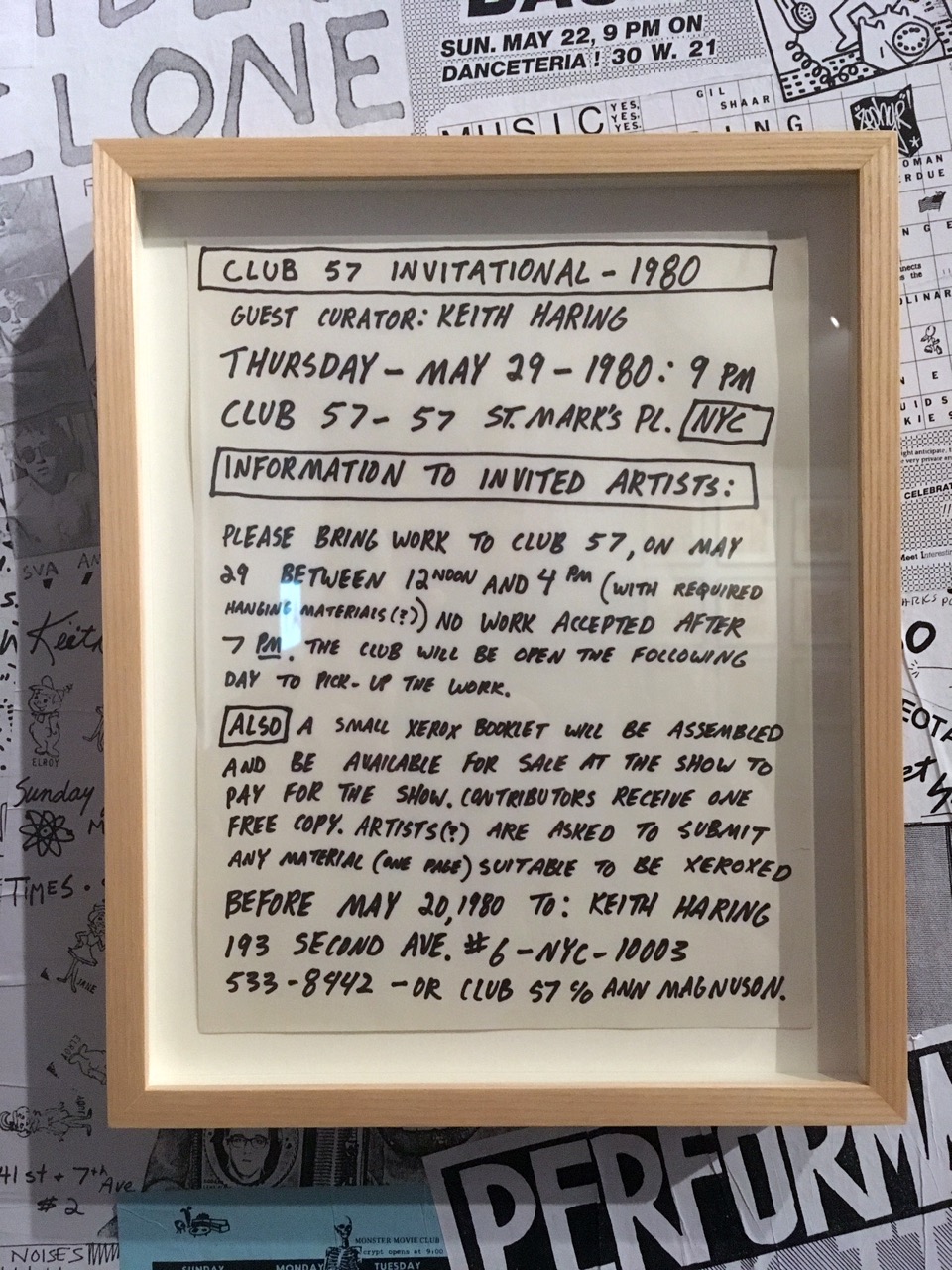

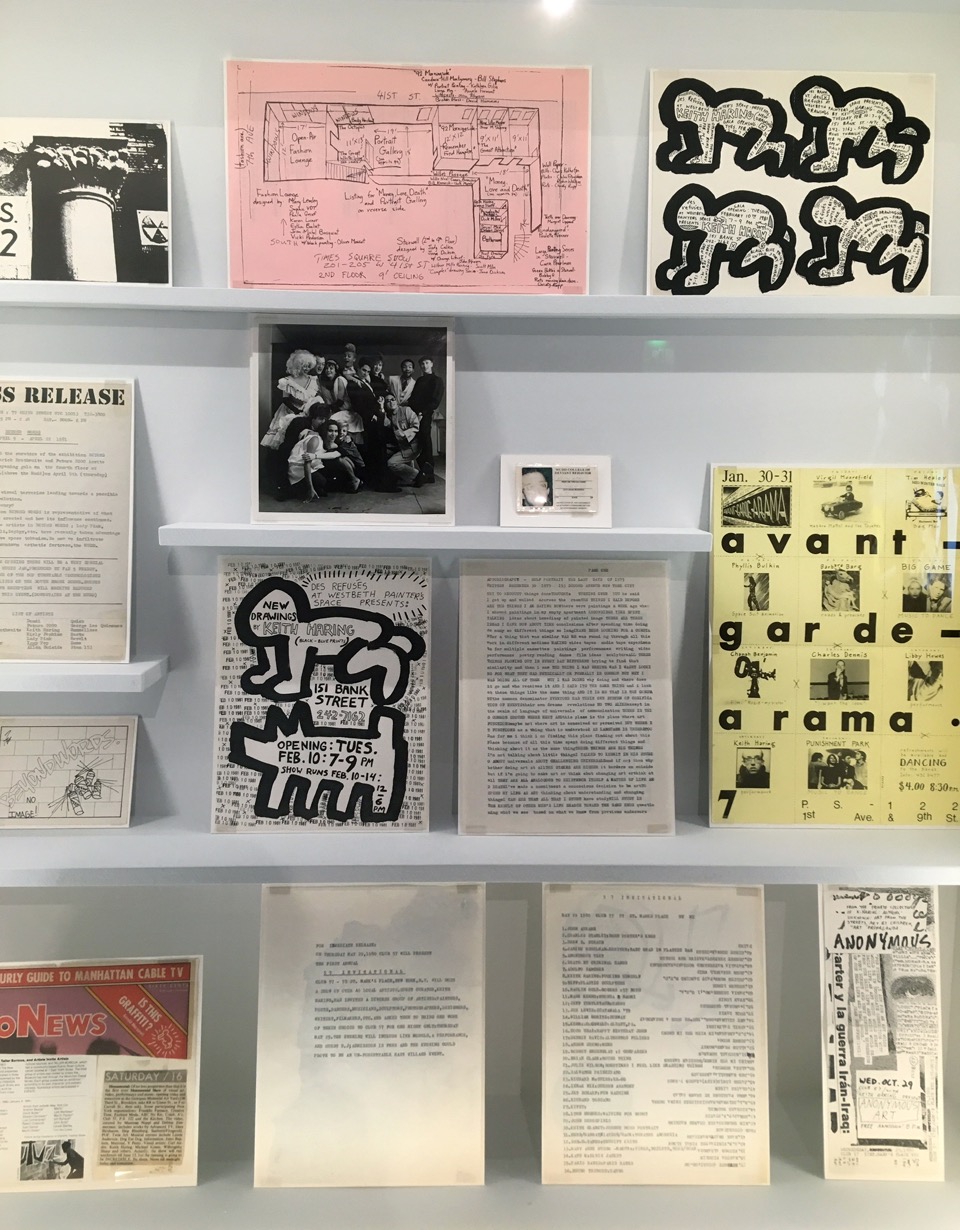

Haring and Liverpool are both known for their political engagement and love of music and fashion. In the impressive Albert Dock buildings on the waterfront at Tate Liverpool, this vibrant show includes more than 85 Haring artworks, from large paintings to small drawings. Also on display are posters, photographs, flyers, invitations and videos that together capture the buzz and crackle of street culture in 1980’s New York.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

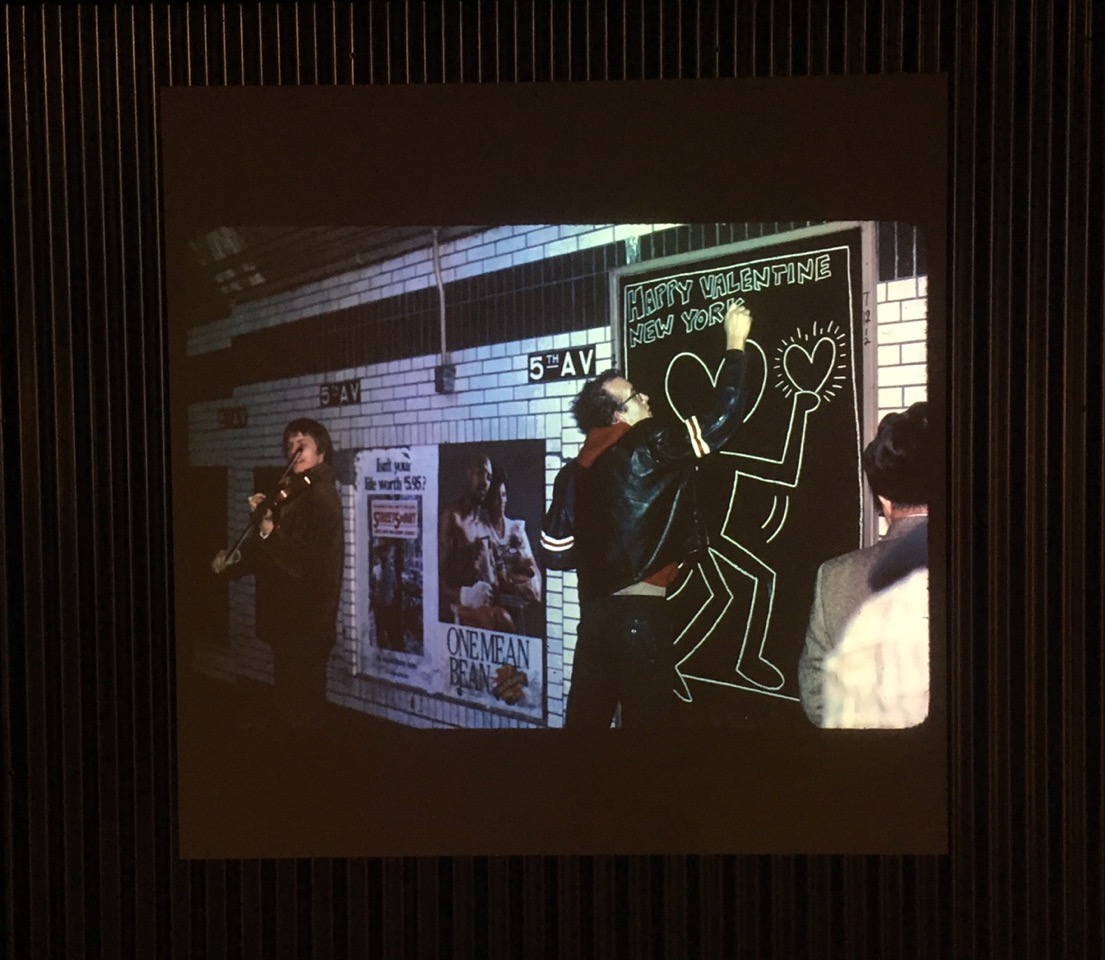

It is the video and old films here that remind us how fast and prolific Keith Haring was in making his mark on art history. His sister Kay says, “Keith had a very distinctive line and he did his drawings so quickly, especially in the subway. Things just came out of his head very quickly when he had the space in front of him.”

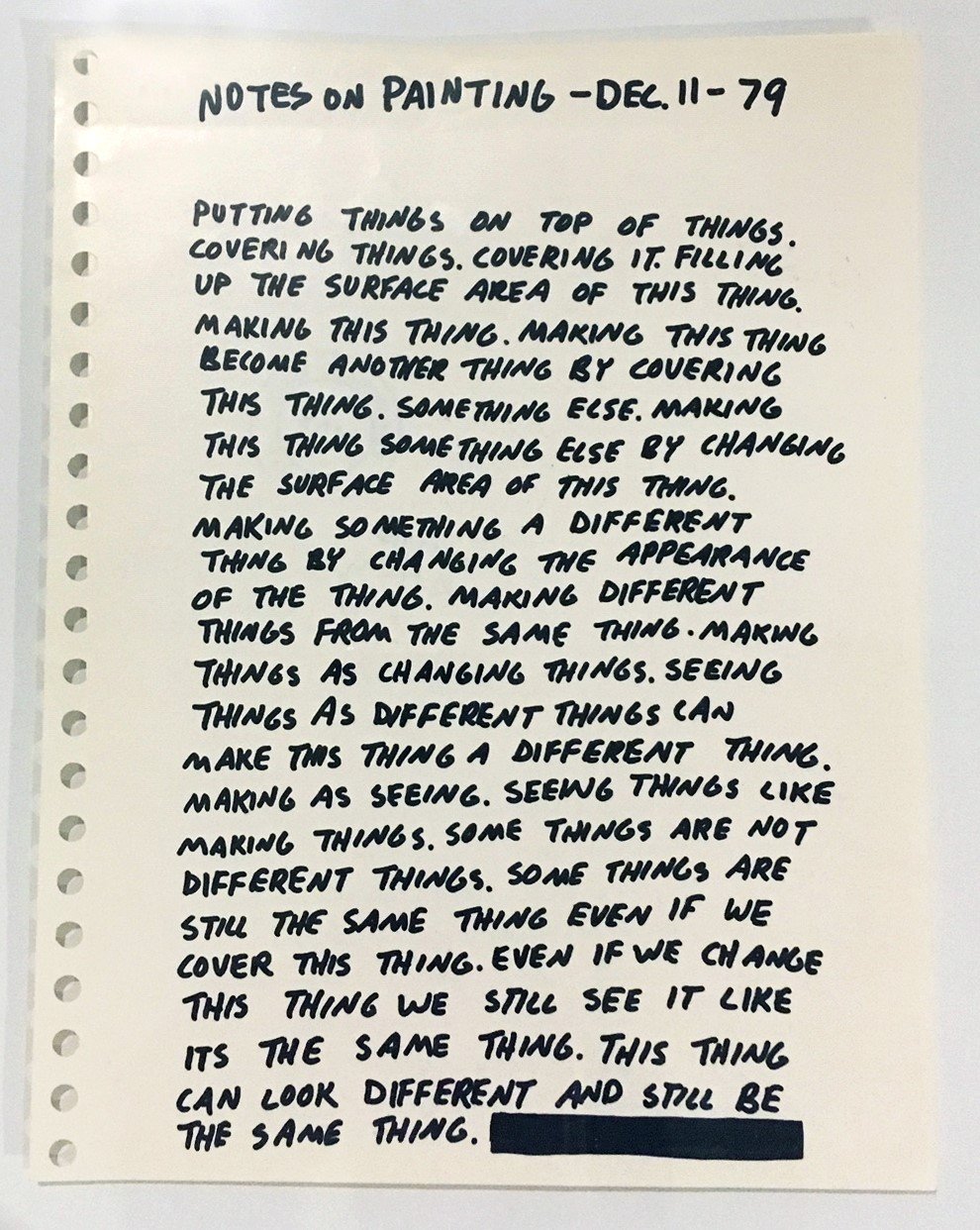

Keith Haring was born in 1958 in Reading, Pittsburgh. Growing up as part of a fairly conservative family, his engineer father taught him some basic cartooning skills that sparked his love of drawing, art and cartoons. After completing his studies at high school, he enrolled in Pittsburgh’s Ivy School of Professional Art. Before long though, accepting he had no real interest in becoming a commercial graphic artist, he dropped out but continued to study on his own.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Between 1976 and 1978 he enrolled in the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York City. He was twenty years old, juggling his day time studies with nights working as a busboy at Danceteria, where Madonna worked as a coat-check girl in the early 80’s.

Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Haring recalled, “Everything was very exciting – living in Greenwich Village, having my own apartment and going to school. And it was great meeting Kenny Scharf and Jean-Michel Basquiat, who became my friends and also wanted to become artists.”

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

However, the studies came to an abrupt end when he was expelled from SVA after he and Jean-Michel Basquiat executed a graffiti art project in one of the school’s interiors.

Haring then took his art to the streets. There are photographs displayed in this show of him drawing on the black, empty spaces on the New York subway walls and one or two actual examples on display. Applying white chalk on these unused advertising panels he started to spread his politically charged, graphic messages to the city. He was still an unknown artist at this time but was very inspired by the immediacy and accessibility of graffiti.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Haring said of this period “I kept seeing more and more of these black spaces, and I drew on them whenever I saw one. Because they were so fragile, people left them alone and respected them; they didn’t rub them out or try to mess them up. It gave them this other power. It was this chalk-white fragile thing in the middle of all this power and tension and violence that the subway was. People were completely enthralled.”

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

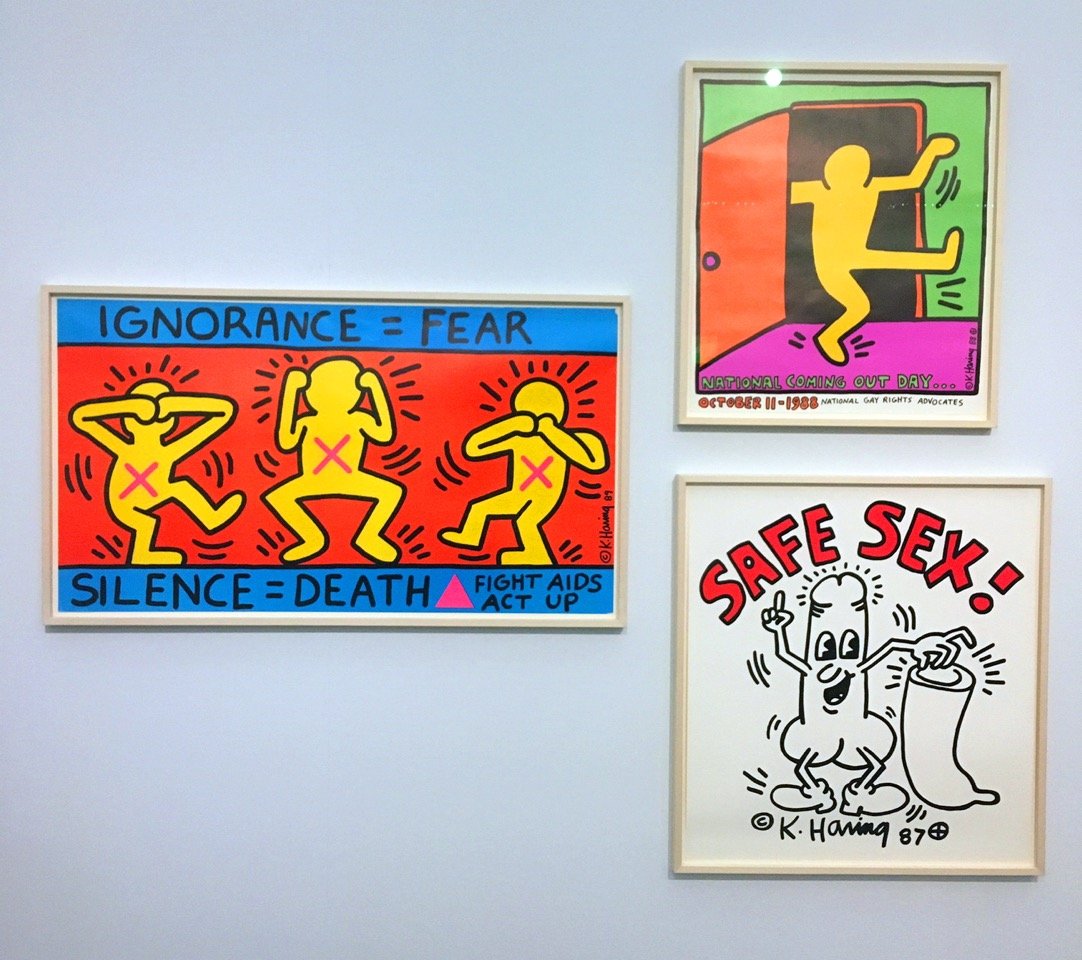

As a gay man growing up in the 70’s and 80’s, this show demonstrates the fact that activism played a key part in Haring’s life and work. Whether as a response to homophobia, apartheid and racism or issues including political dictatorship, aids awareness, capitalism and the environment. The show cleverly takes us on a journey through the art and the accompanying political activism of Haring himself.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

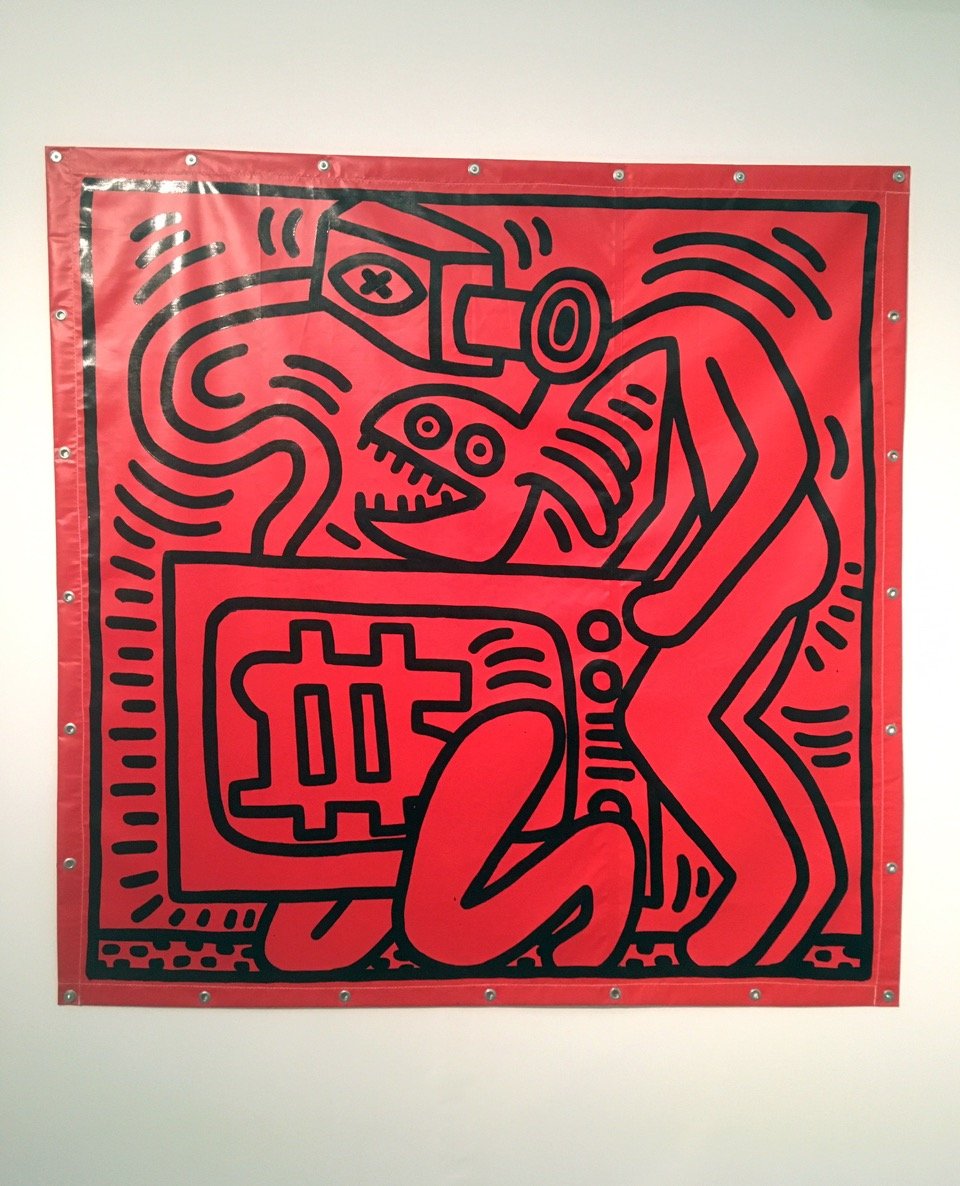

The recurring motifs that we see in Haring’s work are all present in the art on show here. The barking dog, for instance, originated as a simple line drawing that his father Allen used to draw with him. The baby represents “The purest and most positive experience of human existence.” Haring used the atomic symbol regularly too, as having grown up in The Cold War, the threat of nuclear annihilation was always in the air. And he not only produced art on this subject, he also actively added his voice as a nuclear disarmament activist.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

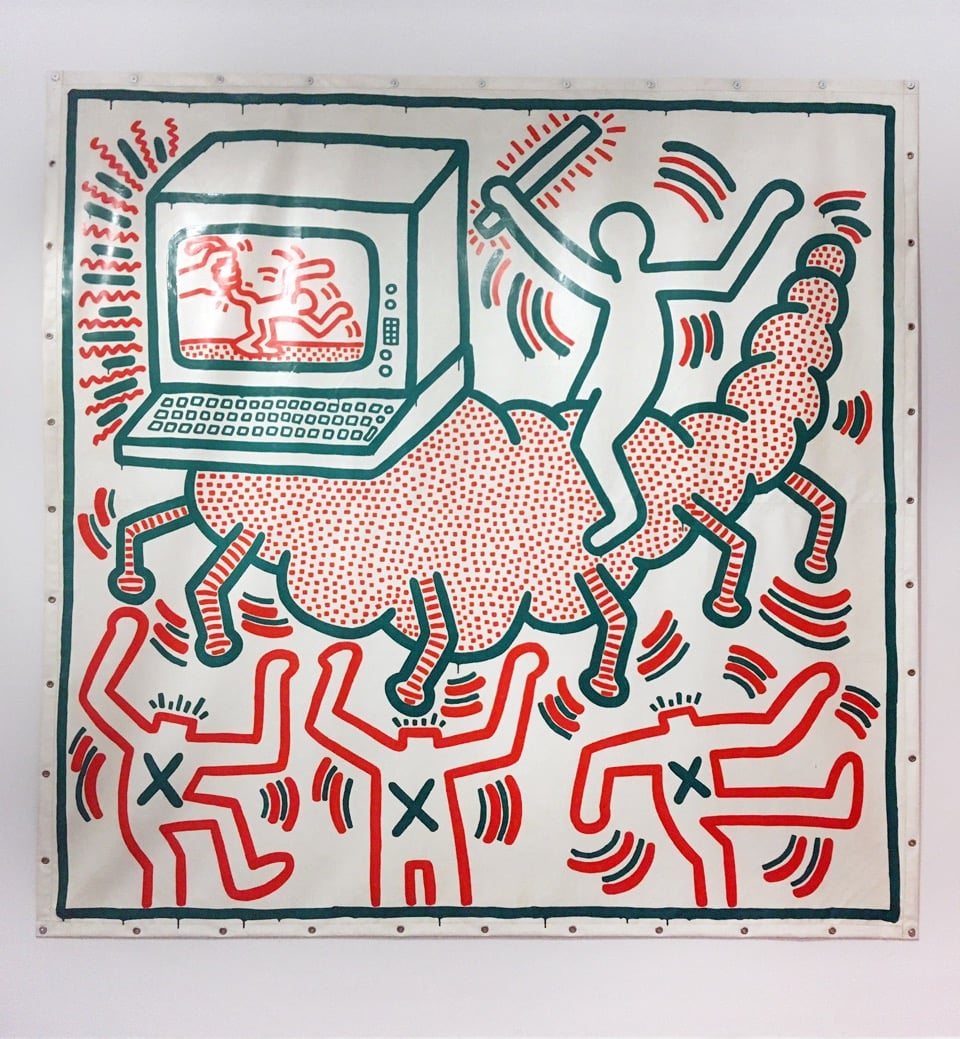

Another graphic you’ll see throughout the Tate show is the TV set. This represents Pop Culture. The transition from black and white TV’s in the mid 60’s to full blown color had a powerful impact on the artist. His enthusiasm for TV coincided with the cultural explosion that was MTV, with whom Haring collaborated enthusiastically.

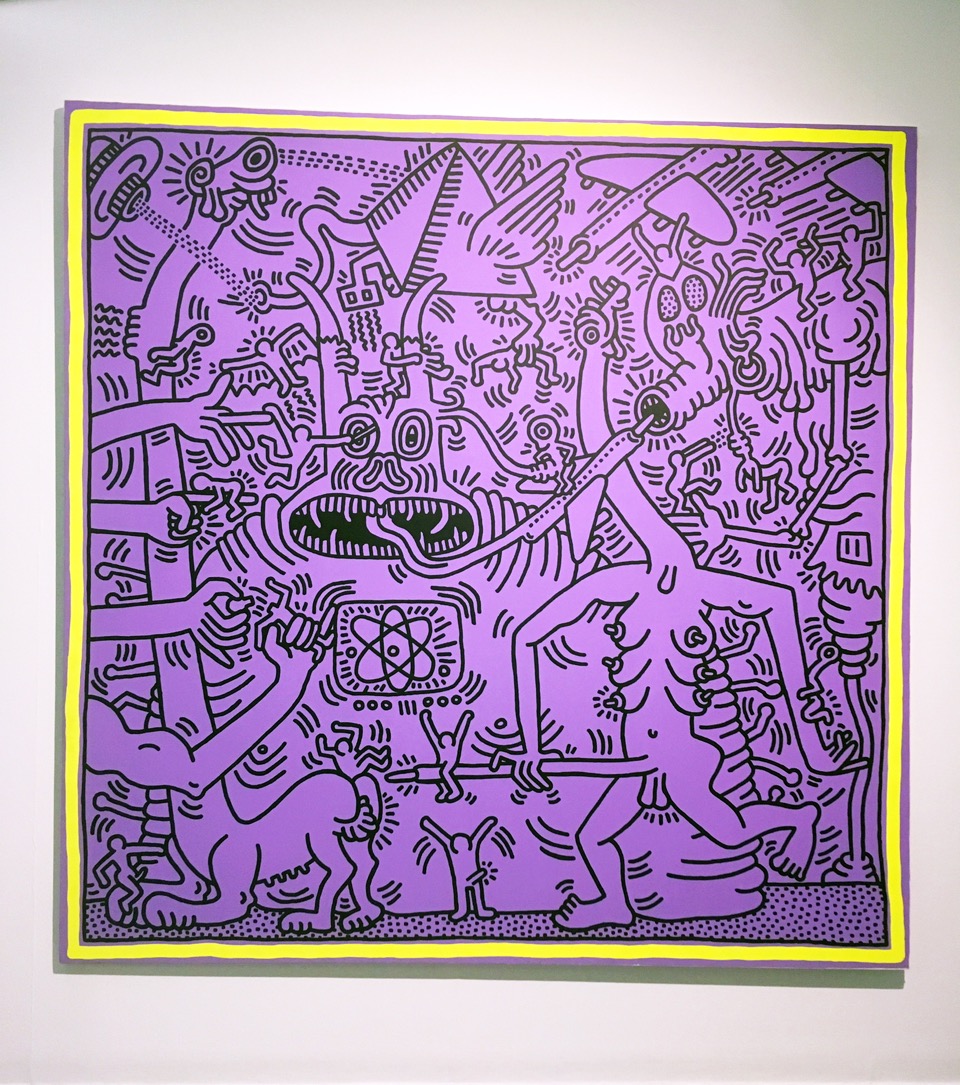

There are other motifs, such as flying saucers, pyramids and the three-eyed face that we see again and again. The dollar signs and crosses (money and religion) are used cynically, making social commentary about mass manipulation in the case of religion and mass consumption, greed and inequality in the case of money. Nothing much seems to have changed between then and now it would seem, as these two themes are still powerfully present in our lives.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Computers and robots also feature prominently and with extraordinary prescience, Haring tuned in to the way computers were revolutionising work and the making of art. On a darker note, the robots symbolise automation and the human creation of technology so advanced that it could ultimately destroy us all.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

His unique graphic style was also quite visceral, inspired by abstract expressionism, Chinese calligraphy, New York graffiti, pop art and underground club culture. Indeed, one of the most vivid experiences on show at The Tate is the immersive ‘Black Light’ installation that Haring put together in 1982. It’s a series of fluorescent works hung on candy-striped fluorescent walls, lit by UV lighting, all set to hip-hop music.

Tate Liverpool’s Keith Haring exhibition is a full frontal sensory experience, both sound and vision. For an artist who celebrated his generation’s counter culture, building on what had happened a few years earlier through the DIY culture of Punk Rock, Haring was keen to bring his art to everybody – a truly public art that reached the biggest possible audience.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

With support and encouragement from friends and fans, including Andy Warhol, this meant embracing the commercial opportunities presented to him; such as tie-ins with Absolut Vodka, an animation for a Times Square billboard and set designs. He also produced watch designs for Swatch, posters for various events, toys, T- shirts, badges and novelty items, all available to buy in the ‘Pop Shop’ he opened in 1986. He was true to his word when he said he wanted to “Break down the barriers between high and low art.”

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

The later work exhibited here is really about life and death. There is a cloud hanging over it, much like the threat of AIDS hung over Haring himself and society as a whole.

Haring himself was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988 but was already truly committed to AIDS activism, producing his famous Safe Sex poster in 1987 and participating in Art Against AIDS, to raise money for the American Foundation for AIDS Research.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

The ‘end of life’ paintings, with their apocalyptic feel are executed in Haring’s signature style but have the feel of Hieronymus Bosch pictures. One shows a body lying down and out of its stomach is spewing a huge cloud of chaos and destruction. It’s disturbing and exhilarating at the same time.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Haring died of Aids-related complications on February 16, 1990, at the age of just 31. Before he passed away, he managed to establish the Keith Haring Foundation with its aim of providing funding and imagery to AIDS organisations and children’s programmes and to expand the audience for Keith Haring’s work.

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

Photograph: Ashley Jouhar. Copyright: Keith Haring Foundation

The brief, explosive period between 1980 and 1990 saw Haring create the bulk of his legacy. One thing this show demonstrates really well is how powerfully political Haring’s work is as well as being as visually impactful now as it ever was.

Keith Haring at Tate Liverpool runs from June 14 to November 10, 2019.