Did the CIA “Weaponize” Pollock’s Paintings?

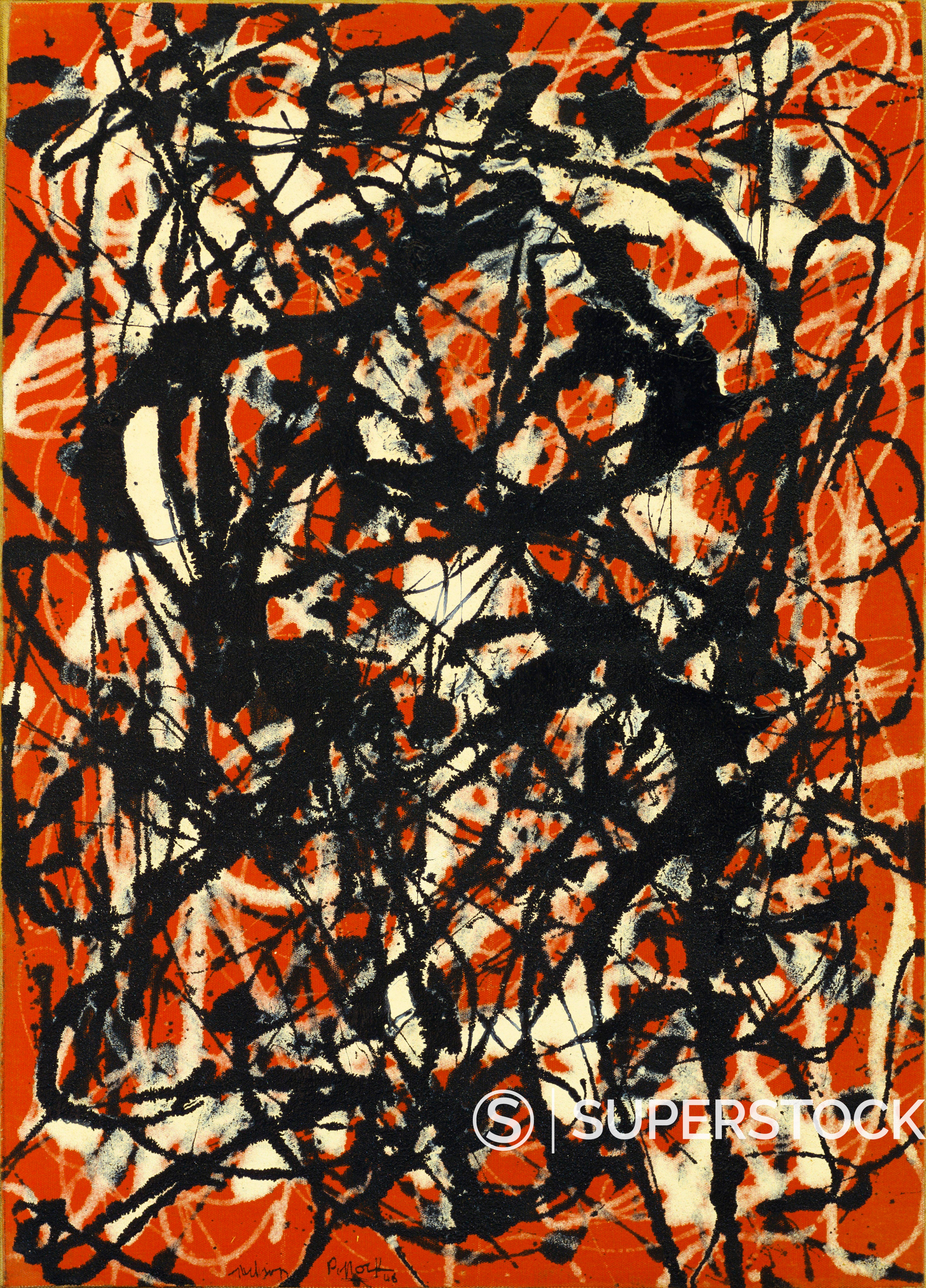

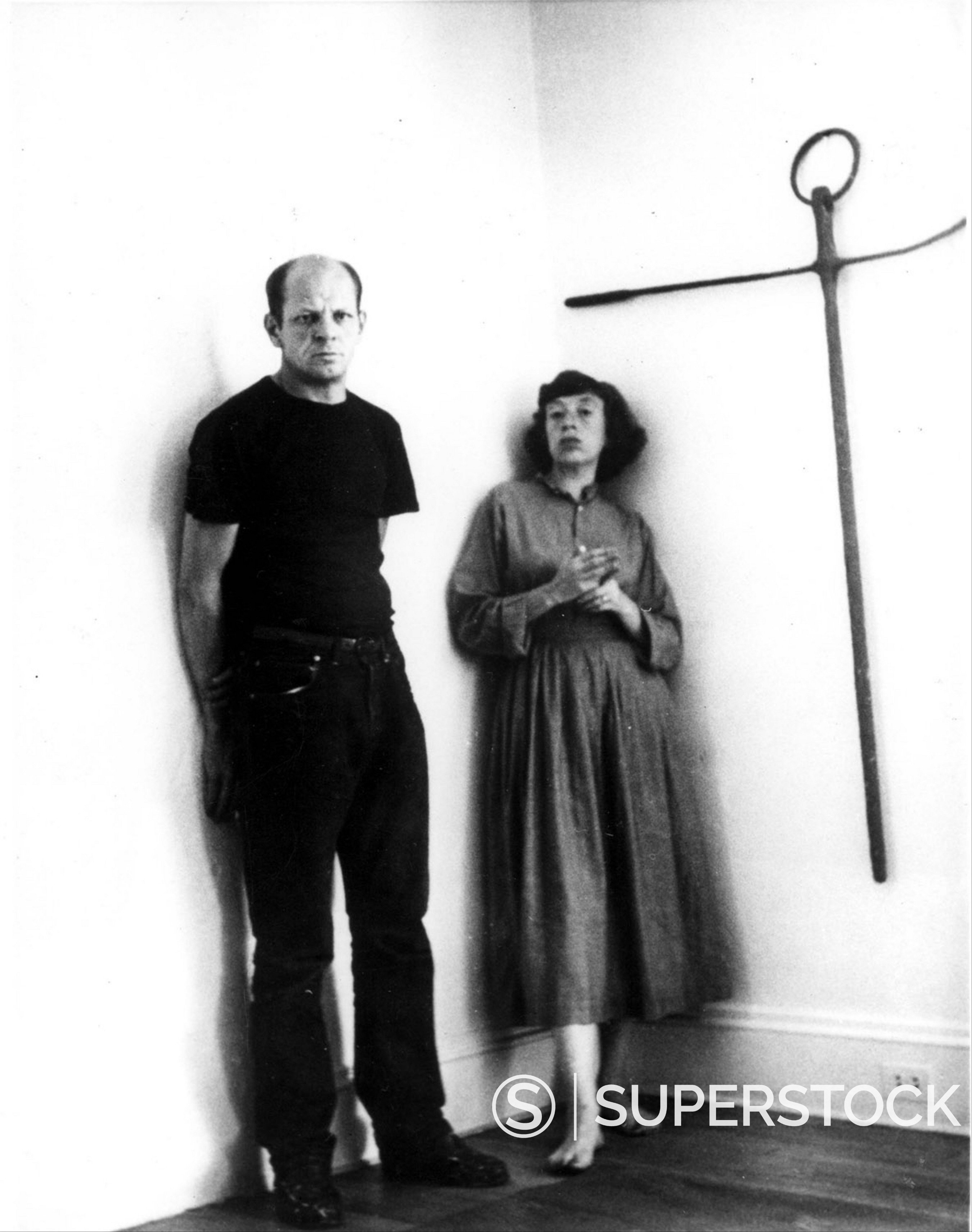

Painter Jackson Pollock, dubbed “Jack the Dripper” by Time magazine, was both admired and influential, but did he work for the CIA?

Not exactly. However, the CIA did use abstract expressionism as part of Cold War propaganda aimed at the Soviet Union. In the ‘50s, American critics were encouraged to contrast the “freedom of expression” represented by Pollock’s work with the grim social realism associated with the European art scene. The political goal was to promote a cultural shift, making New York, not Paris, the epicenter of the art world.

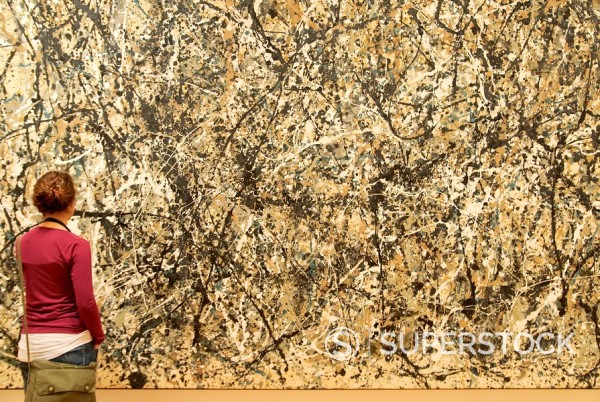

Nelson Rockefeller, whose family ran the Museum of Modern Art, became a vocal champion of the individualism of Pollock’s work. Critics and collectors soon echoed his admiration. A CIA-fronted organization, the Congress for Cultural Freedom, sponsored gallery shows and encouraged mainstream coverage in popular magazines such as Life and Time.

By 1958, a touring exhibit, “The New American Painting,” featuring work by Pollock and other action painters caused a sensation in Paris and later London. Public credit for the funding of the Tate showing in London was attributed to an American multimillionaire art lover. It has since been revealed that the money came from the CIA.

There is no evidence that Pollock himself was aware that he had patrons in such high political places. Personally, his early work was anti-fascist. His most productive years – cut short by depression, alcoholism and ultimately a fatal car crash at 44 – were not focused on political statements.

In 2015, one of Pollock’s paintings joined the short list of the most expensive acquisitions in the art world. A private collector paid David Geffen more than $200 million for “Number 17A,” a work from 1948. The painting represents the height of his so-called “drip period,” which he abandoned to produce a less popular series of works in black on unprimed canvas.