The Tate Gallery, London: How the greyness of Britain colored Van Gogh’s vision.

Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

The Sunflowers, by Vincent Van Gogh is a painting we’ve all seen reproduced in books, on T-shirts, posters, place mats, fridge magnets and teatowels. It’s ubiquitous and people feel that it’s a bit of cliché. But is it an image that no longer deserves our full attention?

Not at all.

At The Tate’s ‘Van Gogh and Britain’ exhibition, you will see how Van Gogh came to paint The Sunflowers and a number of his other masterpieces – and how the painting itself then influenced dozens of other artists and admirers of Van Gogh’s work.

Left to right: Van Gogh, 1888. Christopher Wood, 1925. William Nicholson, 1933. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar.

Left to right: Van Gogh, 1888. Christopher Wood, 1925. William Nicholson, 1933. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar.

This is the premise of the exhibition; it shows you where Van Gogh’s influences were found (many of them in London) and how he navigated his way through those influences and turned them into a painting style entirely his own. This is less easily said about some of the many imitators’ work also on show at this exhibition. Fine painters that they are, the likes of William Nicholson, Vanessa Bell, Samuel John Peploe and Walter Sickert all stole from the Dutch master.

Van Gogh lived in England between 1873 and 1876, working at an art dealer called Goupil & Cie in Covent Garden, where he gained exposure to paintings that would stay with him for the rest of his life. It was here that he also learned about British ‘black and whites’ – prints and reproductions by artists such as Gustave Doré, a French artist, printmaker and illustrator, who often worked in London.

Left to right: Van Gogh, Starry Night, Arles, 1888. Gustave Doré, Evening on The Thames, 1872. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar.

Left to right: Van Gogh, Starry Night, Arles, 1888. Gustave Doré, Evening on The Thames, 1872. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar.

Van Gogh started to collect Doré prints, many on show at The Tate and among them Evening on The Thames, 1872. Van Gogh said of this print, “I crossed Westminster Bridge every morning and evening and know what it looks like early in the morning, and in the winter with snow and fog.” He was inspired to pay homage to it with his painting Starry Night, Arles, 1888.

It’s interesting that Van Gogh, the master of vibrant, swirling colors, was an admirer and collector of graphic black and white prints. Having no formal training as a painter, these prints were key in helping him understand composition and the development of his distinctive drawing and painting style.

Van Gogh loved tramping the streets and was often drawn to the river, walking along The Embankment as he made his way to and from his lodgings in Stockwell, South London. He absorbed all the city’s culture at museums and galleries and would have seen the Dutch artist Meindert Hobbema’s painting The Avenue at Middelharnis, 1689at The National Gallery. This painting, displayed here in the exhibition, made a great impression on him and from then on he frequently used this motif of an avenue of trees leading into the distance, as echoed in his watercolour from 1881 entitled Road in Etten. He mentions it in a letter to his brother Theo too, advising him to go and see the painting in the flesh.

Left to right: Meindert Hobbema, The Avenue at Middelharnis, 1689. Van Gogh, Road in Etten, 1881. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Left to right: Meindert Hobbema, The Avenue at Middelharnis, 1689. Van Gogh, Road in Etten, 1881. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Van Gogh developed an overriding concern for the common man and woman and the hardships they had to endure. He would see daily the full spectrum of London life – from the art he admired in the galleries to the heavy industry of the time and from high society wealth to desperate poverty in the streets. This had a great impact on him and his fledgling role as an artist since he had read about this grinding poverty in the novels of Charles Dickens and it would shape his approach of making “art for the people” and of his choice of artistic subjects.

He said that he often felt low in England but “The black and white and Dickens are things that make up for it all.” He loved Charles Dickens’ books, finding in them a reality that struck a chord with him, saying “My whole life is aimed at making the things from everyday life that Dickens describes.”

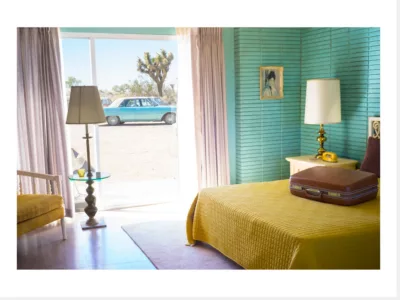

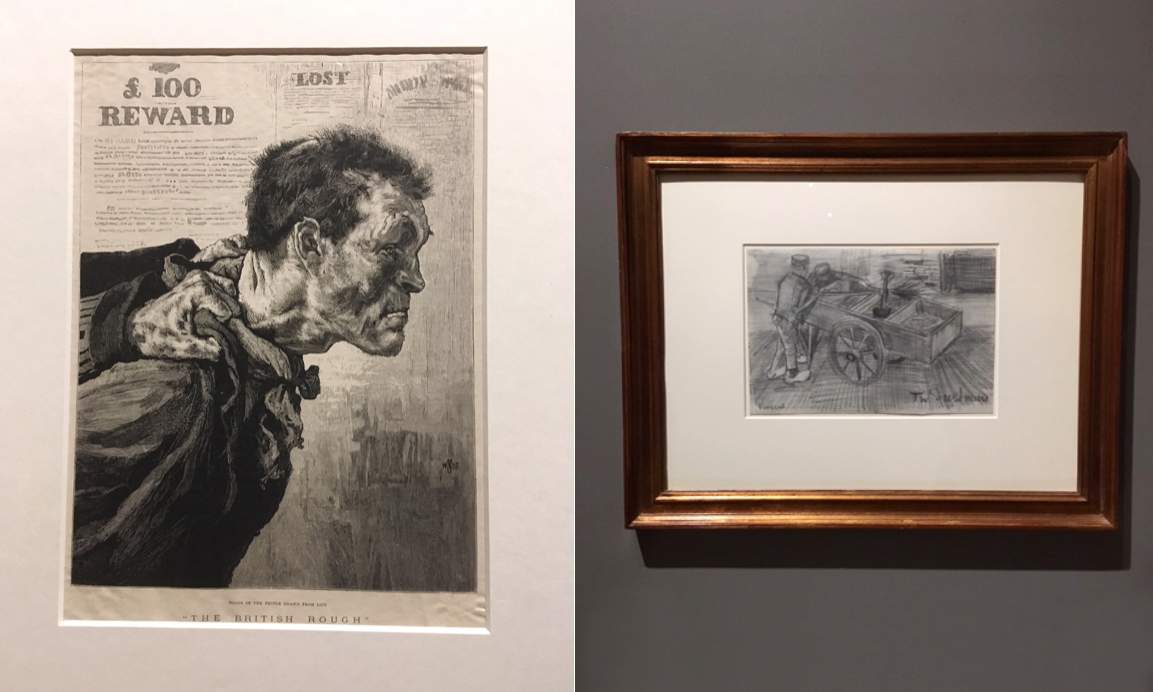

Left to right: Illustration from ‘The Graphic’. Van Gogh, The dustman, 1883. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Left to right: Illustration from ‘The Graphic’. Van Gogh, The dustman, 1883. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Van Gogh was an admirer of The Illustrated London News and a British social reforming newspaper calledThe Graphic, both of which carried the ‘black and whites’ that he was influenced by. While in London he collected a remarkable 2,000 prints, from which he took inspiration throughout his life, some of which feature in The Tate’s show.

In 1886 Van Gogh moved to France from Holland, where he had returned after leaving Britain in 1876 and where he had continued to educate himself as an artist whilst also flirting with the idea of becoming a preacher.

In France, he really developed the mature style for which the world knows him, spending two years in Paris, where he befriended other artists including Toulouse Lautrec. He began to understand the painting style of The Impressionists and tried to master it himself. In Paris, he found himself in the right place at the right time, surrounded by young avant-garde artists, such as Lucien Pissarro, all experimenting with new styles. Over the next two years, Van Gogh transformed his work from the dark, serious hues of his early realist paintings to the colourful textures that became his trademark.

Left to right: Lucien Pissarro, La Maison de la Sourde, Eragny, 1886. Van Gogh, Path in the Woods, 1887. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Left to right: Lucien Pissarro, La Maison de la Sourde, Eragny, 1886. Van Gogh, Path in the Woods, 1887. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

There were The Impressionists, who were already the dominant force in Paris, as well as The Pointillists, who painted with individual dots dabbed on to canvas. Van Gogh absorbed everything and experimented himself with all of the techniques he came across, becoming friends with Émile Bernard and Paul Gauguin along the way. The change in his style and approach to painting led ultimately to Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cezanne being at the forefront of Post-Impressionism, which rejected the naturalistic rendering of light and color championed by The Impressionists for something more revolutionary.

Left to right: Van Gogh, Trunk of an Old Yew Tree, 1888. Van Gogh, Path in the Garden Asylum, 1888. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Left to right: Van Gogh, Trunk of an Old Yew Tree, 1888. Van Gogh, Path in the Garden Asylum, 1888. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

The hectic life he had been leading in Paris began to take its toll on Van Gogh’s health

So before long he moved to Arles in Provence, believing the climate and change of scene would help his art.

He had started collecting examples of Japanese art and the influence of Japanese prints on his work increased, inspiring him to make paintings with bright, dynamic strokes, like Trunk of an Old Yew Treeand Path in the Garden Asylum, both from 1888.

It was in Arles that he also created some of his most famous paintings such as Café Terrace at Night, The Bedroom, The Starry Night, The Sunflowers, The Night Caféand a number of self-portraits, which he planned to swap with Bernard and Gauguin for their own self-portraits.

Left to right: Van Gogh, Self Portrait, 1887. Van Gogh, Self Portrait, 1889. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Left to right: Van Gogh, Self Portrait, 1887. Van Gogh, Self Portrait, 1889. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Eventually Gauguin joined Van Gogh in Arles but ill health and mental issues plagued Van Gogh and contributed to a fractious relationship with Gauguin. He continued to produce many paintings but things came to a head after a dramatic argument with Gauguin on 23 December, 1888, resulting in Van Gogh mutilating his own ear and being admitted to hospital in Arles.

Gauguin left for Paris and Van Gogh decided to have himself admitted as a voluntary patient to the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in nearby Saint-Remy. He continued to work producing paintings such asIrises, Olive Trees andThe Reaper but also suffered further attacks of mental illness, which dogged him for the rest of his days.

Van Gogh, Farms near Auvers, 1890. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Van Gogh, Farms near Auvers, 1890. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

He decided to leave the asylum and travel to Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris in 1890, where he placed himself in the care of Paul Gachet, a doctor and amateur artist. Here, he produced a prolific number of paintings, full of colour and vibrancy. Despite this, on 27 July, 1890, Van Gogh shot himself in the chest and died of his wounds two days later with Theo, his brother at his side. The suicide happened in the countryside outside Auvers-sur-Oise and the painting Farms near Auvers, July 1890,was possibly its location and the last picture he was working on at the time of his death.

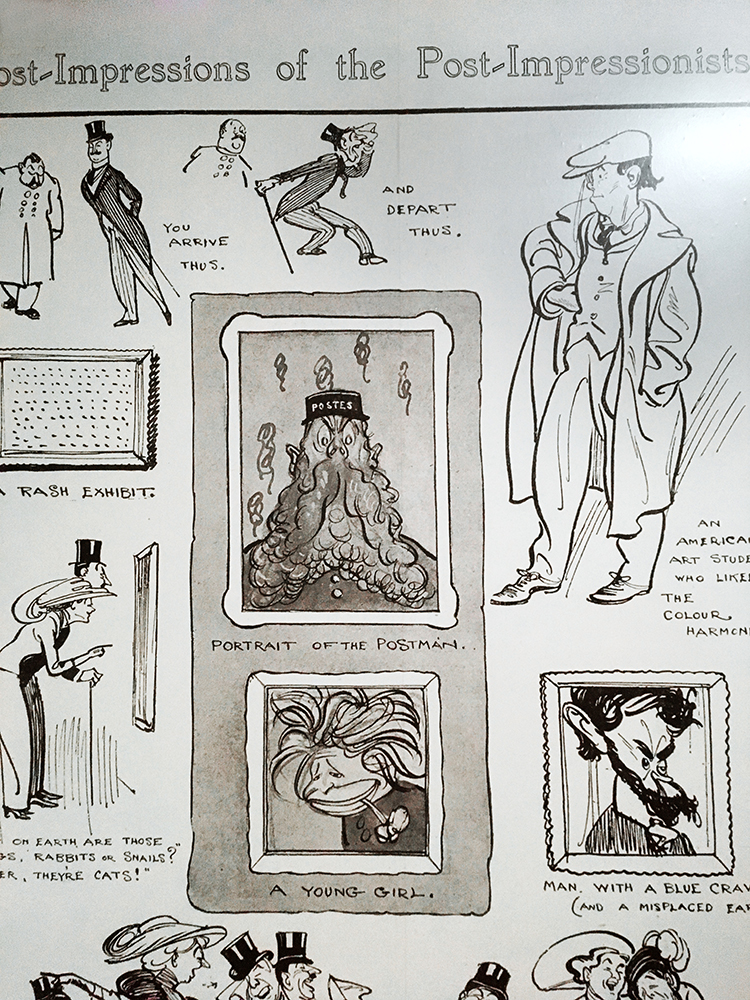

When the Manet and The Post-Impressionists exhibition opened in 1910 at The Grafton Galleries in London Seurat, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne had already all passed away. The show was a public and critical disaster, with the paintings lampooned by cartoons in periodicals of the time. Some of these have been blown up to room size at The Tate, showing how little these artists were rated. However, this show ultimately became one of the most important moments in the history of modern art. Virginia Woolf said, “On or about December 1910, human character changed.”

Page from periodical, ridiculing the Manet and The Post-Impressionists show, 1910. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Page from periodical, ridiculing the Manet and The Post-Impressionists show, 1910. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Whilst it took some time for the public and critics to accept Post-Impressionism, fellow artists were quick to respond and embrace the visual power of this movement. Artists such as Spencer Gore, Walter Sickert, The Camden Town Group and Harold Gilman adopted Van Gogh’s approach to color and brush stroke technique, creating British takes on his subject matter, as shown at the top of this review with The Sunflowers.

The influential British painter Francis Bacon said that “Van Gogh is one of my great heroes”. Bacon’s application of paint was heavily influenced by Van Gogh’s and he felt that the way paint was applied to a canvas heightened the intensity of the reality. He read his letters and understood the importance to Van Gogh of the figure on the road, referencing Van Gogh’s Painter on the Road to Tarascon and producing his own painting called Study for portrait of Van Gogh IV in 1957.

Left to right: Phaidon Press book showing Van Gogh’s Painter on the Road to Tarascon. Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait of Van Gogh IV, 1957. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Left to right: Phaidon Press book showing Van Gogh’s Painter on the Road to Tarascon. Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait of Van Gogh IV, 1957. Photograph by Ashley Jouhar

Tragically, Van Gogh had little success in life and was generally considered to be a madman and a failure. Legend has it that he only ever sold one painting in his lifetime. Today though, he is considered to be one of the greatest and most influential painters in history.

What would he make of that, a little over a century after his death?